The 'Curing' of Australia’s First Transgender Man

One Irish maid lived as a man in 19th-century Melbourne for decades. The horrifying story of his discovery and “treatment” speaks to attitudes about transgender people that circulate to this day.

Ellen Tremaye was not like most of the other passengers aboard the Ocean Monarch, a ship sailing from Ireland to Victoria, Australia in 1856. Though the 26-year-old, Irish domestic servant was traveling alone, she brought along a trunk full of men’s clothes labeled “Edward de Lacy Evans,” fueling speculation that she had been abandoned by a suitor after being tricked into bringing his belongings aboard. Then there was her unusual behavior: She wore the same green dress every day, but with trousers and a man’s shirt underneath. She told her fellow passengers that she was going to marry her ship-mate, Mary Delahunty, as soon as they reached Australia, and she reportedly had “intimate friendships” with two other women who shared her bunk at various points in the voyage.

In the late 1800s, Australia was a collection of untamed colonies. Like the American West, it was in the throes of a gold rush, overrun by outlaws, and gradually being settled by increasing numbers of white people. At the same time, it was still governed by Christian and Anglo-Saxon social mores, with male public officials claiming that the declining birth rate could be attributed to “selfish women” who suffered from an overabundance of “love of luxury and social pleasures.”

When Tremaye arrived, she found a job as a maid for a married couple in Bacchus Marsh, northwest of Melbourne. One day when the man of the house was out of town, Tremaye spent the night with his wife, and the husband horsewhipped her when he returned, according to research by Lucy Chesser in the Journal of Women’s History.

Tremaye soon left the job and traveled to Melbourne. We don’t know precisely what drove what happened next, but at this point Tremaye transformed forever. He began using the name Edward De Lacy Evans, started dressing in men’s clothes, and married Delahunty. (In line with Evans’ apparent wish to live as a man, I’ll use male pronouns from this point forward.)

According to accounts from the time, the couple “did not live comfortably together,” and they separated in 1862.

Over the next two decades, Evans went on to remarry twice, all while working as a miner and blacksmith around Australia’s southeast, according to a history of Evans by the historian Mimi Colligan.

It seemed that Evans’ maleness was accepted by both his wives and neighbors, though his fellow miners occasionally referred to him as “old woman,” Colligan points out, suggesting that his physical womanhood might have been an open secret.

Evans’ third wife, Julia Marquand, eventually had a child by her brother-in-law, sparking bitterness between the couple. He began lashing out at Marquand and her daughter, and he gradually descended into a deep depression.

In 1879, Evans was committed to the Lunacy Ward of the Bendigo Hospital and diagnosed with “amentia,” a general, anachronistic term for mental illness. To avoid being discovered, Evans simply refused to bathe.

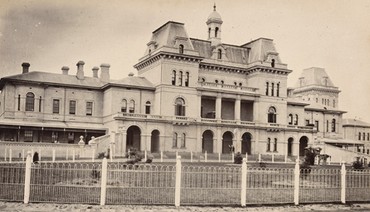

After six weeks, however, he was moved to the Kew Asylum, a psychiatric hospital in the Melbourne suburbs. There, he was stripped, and his gender discovered.

“The fellers there took hold o’ me to give me a bath, an’ they stripped me to put me in the water, an’ then they saw the mistake. One feller ran off as if he was frightened; the others looked thunderstruck an’ couldn't speak. I was handed over to the women, and they dressed me up in frocks and petticoats,” Evans later said of the experience.

Doctors diagnosed him with “cerebral mania” and “mental weakness,” and offered him only female attire to wear. He refused to wear it, or to eat, for days at a time. Over the course of Evans’ three-month treatment, physicians subjected him to extensive vaginal and rectal probing, during which he reportedly “sobbed and wept.”

Marquand later claimed she had no knowledge of Evans’ biological sex—he never let her see him changing, she would later attest. Colligan points out that this is not as far-fetched as it sounds: A few other documented cases of women posing as men at the time involved stories of strap-on dildos used for sex. For Marquand, though, this might also have been a face-saving excuse. She also later claimed that she did not know how she got pregnant, and that she must have mistaken an intruding “real man” for Evans when he snuck into her house.

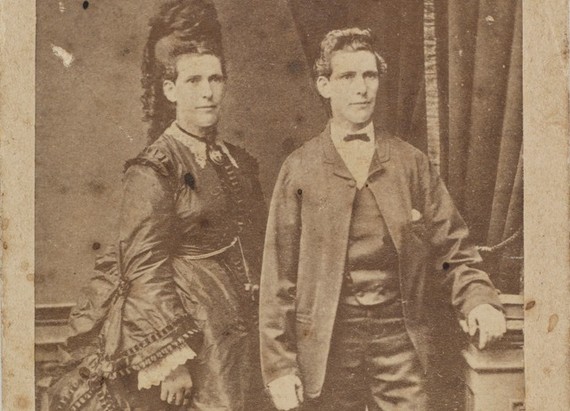

Evans’ exposure caused, to put it mildly, an incredible stir. One local photographer snuck into the hospital and took photos of Evans dressed in both male and female clothing, as well as in a straight jacket. Local sideshow operators offered the hospital 5 Australian pounds a week to display Evans as an oddity.

After his release, Evans did appear in one such traveling carnival, where reporters noted that he appeared “weak and half-witted” from the ordeal. Sideshows billed him as “The Wonderful Male Impersonator” and a pamphlet about his life, The Man-Woman Mystery, was published in 1880.

The news coverage in the immediate aftermath of the scandal speaks volumes about heteronormative sentiment in the late 1800s. From reading Chesser and Colligan’s accounts, any kind of gender-bending was seen as, at best, a pathology, and at worst, a crime.

Within 24 hours of Evans being outed, a local paper called the Advertiser breathlessly wrote it was, “one of the most unparalleled impostures ... which it has ever been the province of the press of these colonies to chronicle, and we might even add is unprecedented in the annals of the whole world,” as Chesser found.

Other coverage promulgated the idea, which occasionally surfaces to this day, that transgender people are motivated by eroticism, rather than by the feeling that they are trapped in the wrong kind of body.

One newspaper attributed his cross-dressing to nymphomania, writing, “It is evident … that the woman must have been mad on the subject of sex from the time she left Ireland dressed as a woman,” and later celebrated Evans' return to femininity after “treatment:” “Her breasts have almost regained their normal condition; the wrinkles in her face have disappeared, her arms are becoming fleshy, and the scars and marks on them being eradicated.”

The fact that Evans had been discovered while in an asylum only bolstered the idea that he was mentally ill.

"Why she was guilty of the criminal deceptions which she has practised on three women will be understood by medical men as results of the only insanity that effects her, but cannot be explained here," the Bendigo Independent wrote.

It wasn’t Evans’ cross-dressing that so disturbed his contemporaries—there had been other, contemporary instances of women donning men’s garb as a joke or performance—but the fact that he had duped society, and seemingly his own wives, for so long.

News reports used quotation marks around both male and female pronouns in describing Evans’ life, somehow implying that he wasn’t truly either. Some reporters speculated that Evans must have become pregnant out of wedlock while on the sea voyage and took on a male identity to hide his shame.

After Evans’ release from the hospital, newspapers reported with satisfaction that he had returned to wearing dresses and looked “quite feminine,” and that he would not again attempt to “unsex herself.”

In the end, Evans wasn’t able to reap much of a fortune from his sideshow appearances. The following year he moved into a Melbourne poorhouse, where he went by “Mrs. De Lacy Evans” and lived for the next 21 years, wearing drab, gray dresses and tending a garden. He died of the flu in 1901.

“The story of Ellen Tremayne is an example of the lengths to which some women had to go in order to live as they wished,” Colligan wrote. “She gave false statements at her ‘marriages’, risked ostracism, and endured exposure to a gaping audience as a show-freak. However, dressing and living as men perhaps gave her a sense of power lacking in her female role.”

No comments:

Post a Comment